Circle-Lust Continues

This blog entry was written by Bryan Pierce of Perceptual Edge.

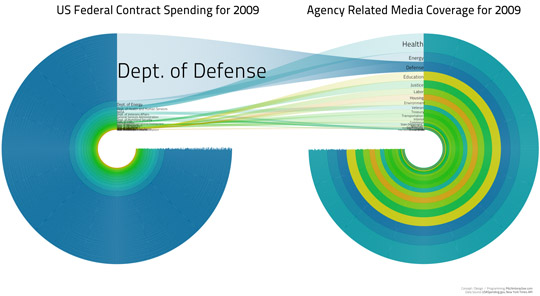

Last week Stephen published an article entitled, “Our Irresistible Fascination with All Things Circular,” which describes how people’s seemingly innate love for circles has led to the creation of many dysfunctional graphs, such as pie charts. Today, another example of a poorly designed circular graph came to our attention. A couple months ago, Sunlight Labs hosted a contest called “Design for America,” which asked designers to create displays of government information for the purpose of making “government data more accessible and comprehensible to the American public.” A couple days ago, they announced the winners. In the data visualization category there are plenty of examples of what not to do, the worst of which appears below.

This display is supposed to be used to compare the 2009 US Federal Contract Spending for several sectors to the amount of Media Coverage that those sectors received during the year. As you can see, the designers seem to have fallen into the same sort of circle-lust that Stephen wrote about last week. In this case, the circular shape seems to be entirely arbitrary, because the quantitative data is encoded only by the thickness of the rings. These circles serve the same purpose as stacked-bar graphs; they’ve just been stretched out and distorted into a circular shape.

Ignoring the uselessness of the circular design for a moment, what does this visualization tell us? The only thing it tells me is that Defense spending was vastly under-reported in the media during 2009 while Health and Energy spending were comparatively over-reported. Without a lot of effort, I can’t make meaningful comparisons between the information in the other sectors, because they’re too small and hard to see, and I can’t even make comparisons between the three largest sectors with much accuracy. It’s also difficult to read the names of the smaller sectors because they overlap.

Although it might not be as sexy, two horizontal bar graphs next to one another would work better: one for Federal Contract Spending and one for Media Coverage. The Federal Contract Spending graph could be sorted from highest to lowest and the Media Coverage graph could present the bars in the same order. This would make it very easy to compare a sector’s spending and media coverage (because they’d be aligned in a row), it would make exceptions jump out (because there’d be a difference in the length of the bar in the Media Coverage graph compared to its neighboring bars), and it would be easy to read the names of all the sectors. It would still be hard to decode the contract spending in some of the smaller sectors accurately (because their bars would be so much smaller than the Dept. of Defense bar), but at least all of the bars would share a labeled quantitative scale, which would make the task easier.

Another useful alternative, which would put even more focus onto the relationship between Federal Contract Spending and Media Coverage, while making the exceptions jump out, would be a scatterplot that displayed Federal Contract Spending on the x-axis and Media Coverage on the y-axis.

It is unfortunate that most of the winners of Design for America contest don’t represent useful designs. The fact that the circular graph above was a winner either means that the judges of the contest had a terrible selection of designs to choose from, or that the judges don’t understand data visualization. This is sad, not just because people are being given $5,000 prizes for impoverished displays, but because this information is important and it could benefit people if it was presented in a useful way.

-Bryan

18 Comments on “Circle-Lust Continues”

Hi Bryan,

I appreciate the criticism. I really do.

The first iterations we created were actually just bar graphs and it is our process to start with very familiar graphs, diagrams and visual tools when we create our data visualization work. However, our primary goal is to explore compelling and engaging ways that break away from traditional forms of visualizations. Simply put, we believe there are many complex relationships in data and that traditional methodologies simply do not illustrate or emphasis the story being told. We are entering a new era of exploring data that calls for new ways to visualize this data. And this new era includes visual artists as the engineers developing the visualizations. I embrace this and am sorry to see you do not.

The real story being told here is not to illustrate exactly how much funding when into a particular agency. It demonstrates that our government spends a massive amount of money on Defense in relation to other agencies. So much more spending that the other agencies become obscured and minuscule in comparison. Compare this with how much we read/write about these topics and we have a comparison for how much our government spends vs. how much the media will actually cover these important aspects. This is a perfectly reasonable comparison.

Are circular visualizations overused? Yes and you’re welcome to say this is in the overused circular visualization category. But circles work really well in a lot of visualizations we do. In this particular visualization we tried using just bar graphs. However, I’m glad we took this further to explore a more compelling and visually engaging way of telling the story.

Wes,

There is so much more to this story that you could have communicated. Important information has become buried in the design, and the little that can be seen cannot be seen clearly. If all you wanted to say was that “our government spends a massive amount of money on Defense in relation to other agencies,” this could have been said much more elegantly and clearly.

There’s plenty of room for new ways of visualizing quantitative information, but there is no room for new ways that don’t work. Innovations that work less well than what already exists aren’t useful. Attempts to innovate that ignore what we already know are misguided and wasteful.

You wrote:

As someone who wishes to support the new era of exploring data, you should know better than to draw this illogical conclusion. The fact that we have found your design ineffective does not mean that we don’t embrace the work of visual artists. I welcome contributions to the field of data visualization from any source, especially those involved in other areas of visual design. The criteria of effectiveness that I use to evaluate all data visualizations are the same, however, no matter whose contribution I’m reviewing. Artists who venture into the field don’t get to be evaluated on different terms. To produce effective data visualizations, you must understand how people see and how they think when interacting with graphics. You must take advantage of this understanding to create visualizations that inform. If they also entertain, all the better, but they must inform.

You wrote, “We believe there are many complex relationships in data and that traditional methodologies simply do not illustrate.” You’ll get argument no from us. Your design, however, does not address a complex relationship. You’ve unnecessarily complicated a relationship that is quite simple.

You agree that circular designs are overused in data visualization, but believe that they “work really well” in many visualizations that you create. That’s certainly possible, but I’ve seen no evidence of this. I invite you to post an example here and let the people who read this blog—primarily people who care a great deal about data visualization and know a thing or two about it—assess its effectiveness.

It is incredibly important that we find ways to engage people with data visualizations, but the engagement only matters if people are actually engaged with the data. Looking at the pretty circles of color, no matter how much they appeal to us, means nothing if we don’t walk away from the experience better informed. Not just better informed, in fact, but accurately informed as much as possible about the things that matter.

Steve

Hi Brian. I’m a big fan of Stephen’s work and this is a nice blog. However, it would’ve been most helpful to me to see an actual proposed ‘before’/’after’ comparison instead of just a description of how to improve it.

I do think that this piece may have been intended more as an art piece than as a way to effectively communicate a large amount of information, and in that area, to my eyes it does succeed as an interesting and novel, although ineffective at showing anything other than very large variations, method for visualization of data.

You suggested we use bar graphs and scatter plots. This and everything else you say suggests that you don’t understand the point of this visualization. I’m not disagreeing with what you say. There is a much more simplified way to represent this data. The point is that we explore compelling ways to represent information and this is one of those endeavors. I don’t think you understand the meaning of this. So I will leave it there and will let time take its course.

Wes, I like what you’ve done here, but I think the main reason the circles are problematic is that the data is portrayed entirely accurately without them. Imagine taking the rectangular area that contains the agency names, and omit the remainder of the circles. The takeaway is exactly the same. This means the circles are essentially superfluous.

I have personally always found two big challenges in data visualization: avoiding making things look pretty, and avoiding editorializing the data. There are many current trends (especially in the infographics realm) that seem to aestheticize data. But the real goal of data visualization is to make the information easier to understand at a glance than it would be if presented quantitatively…which requires paring the visuals down to the absolute minimum.

Wes,

You must not be familiar with my work, otherwise you would know better than to think that I don’t understand what it means to “explore compelling ways to represent information.” I’ve dedicated my life to this pursuit. Important information like the media’s misaligned priorities should be presented in ways that promote the clear understanding that is needed to compel informed action. Experiment all you want, but test your designs, not by asking people, “Do you like it?”, but by determining if they actually understand what they see and find it useful. And don’t be satisfied with saying little when you could say much more that people need to hear.

Wes, for me, this visualization caused cognitive dissonance. By that I mean I immediately stopped looking for knowledge and in fact shied away from looking for insight. I had to force myself to look for information there – it was not a comfortable experience.

So I guess I found it compelling, but probably not in the way you intended as it compelled me away from understanding and exploration.

I like your thought over on twitter though – to offer up the data for a remix

My first thought upon seeing this visualization was that I’d like access to the raw data so I could make a simple bar chart. This visualization prioritizes design so far above the information that most of the information is completely lost.

Beyond some imbalance between defense spending and reporting, I can’t tell what’s going on here at all. I’m not compelled to do anything (like re-tweet it, or write a letter to an editor, or write my representative) by this visualization because…well, there’s hardly any information I can draw from it.

I’m reminded of David Ogilvy’s section on “the cult of creativity” from the 2nd chapter of Ogilvy on Advertising. “If it doesn’t sell, it isn’t creative” and “Originality is the most dangerous word in advertising” are two adages I keep close at all times. Or, as Stephen put it a while back, “Most of what we can do to make the world a better place involves, not doing the unprecedented, but doing what matters and what works.”

We can learn a lot from advertisers who dedicated their lives to compelling their audiences to change their behavior (i.e. take out their wallets). It doesn’t involve dazzling people, it involves effective communication.

@pitchinteractive has posted a pic of what a stacked bar chart of the data would look like. http://twitpic.com/1rn1nz

Would enjoy hearing your thoughts.

Rob,

A stacked bar graph is not an effective solution. Bryan of Perceptual Edge will post examples of useful solutions tomorrow.

Stephen,

Looking forward to seeing them.

The contest called for designers to make “government data more accessible and comprehensible to the American public.” Compelling and engaging designs that do not work do not help the American public to comprehend the data and should not have won this prize.

Tim, you’re right, it would have been useful for me to show some potential redesigns instead of just describing them. Originally, I didn’t create them because I couldn’t decode the values in the original graph with enough accuracy. However, following your comment, I found the original data on Wes’s website, so here they are. These graphs are just a couple that I put together quickly as potential redesigns. I’m sure they could be improved further and they certainly aren’t the only designs that would work effectively. If readers have ideas for improvements or other redesigns, I encourage them to post them too.

The first redesign that I mentioned consists of two horizontal bar graphs as shown below:

(Click to enlarge.)

I think this would be the best design for a general audience. As I mentioned above we still can’t accurately decode the values of the sectors with less spending, but the labels are easy to read and several instances of disproportionate reporting jump out at us (for instance, it’s easy to see that General Services had no stories about it, while the Department of Education had the fourth highest amount, despite ranking fourth lowest in contract spending).

The second possible redesign that I mentioned was a scatterplot. This solution wouldn’t work as well as the bar graphs for a general audience, but if this information were being presented to a group that has had some exposure to scatterplots, it would do the job well.

(Click to enlarge.)

In this case, the scatterplot on the left shows that Defense spending represents a significant outlier compared to the other variables (which have all been squished into the left-most portion of the graph). In the scatterplot on the right, I’ve filtered out the Defense outlier so that we can also focus on the relationship between Contract Spending and Media Coverage in the other sectors. As you can see, there is a very loose positive correlation, meaning that, in general as Contract Spending increases, so does the number of New York Times stories, but the correlation is weak and there are many outliers.

-Bryan

I hate to say it, but I believe that Wes’s mission is entirely different from the staff and disciples of Perceptual Edge.

In his post, he says his “…primary goal is to explore compelling and engaging ways that break away from traditional forms of visualizations.”, As if traditional forms are somehow flawed, outdated in some other way obsolete….

While this “exploration” is potentially eye-catching, it blatantly ignores accuracy and precision, arguably more important objectives of data visualization. I am sure some would find this graphic engaging and/or compelling, but it doesn’t function to present a decipherable representation of reality.

Unfortunately, it seems that (like all too many others things in the world) this is designed to create value for the reader – by substituting flash for substance.

Simple-mindedly distorting a stacked bar graph (itself a potentially poor choice) 360 degrees will no doubt capture the attention of innocent and uninterested bystanders, but the important story contained within the data has also most certainly been twisted beyond intelligibility. And I for one fail to see any value in that.

The contest’s goal was to make “government data more accessible and comprehensible to the American public.”

But as Wes replied, initially he started with bar graphs and then tried to emphasize a story he found through them:

“The real story being told here is not to illustrate exactly how much funding when into a particular agency. It demonstrates that our government spends a massive amount of money on Defense in relation to other agencies. So much more spending that the other agencies become obscured and minuscule in comparison. ”

Yet the contest never asked to draw a conclusion of some sort, it only asked to find a way for the general public to be able to draw their own conclusions without confusion/misdirection. In the circle graph form, no person would be able to tell at a glance what the overall data actually says without looking at the website. I mistakenly thought at first Labor and Justice were equal!?!

Bryan’s graphs meets the contest criteria and allows any viewer to draw their own conclusions from that.

You know, I think Jonas hit this one on the head. The ‘rectangular’ area without the distraction of the pinwheels is informative, impactful and beautiful.

Try masking the pinwheels out, the graphic becomes immediately clearer without losing any of its aesthetic impact.

There is so much overlapping action it might be helpful to make the graphic slightly interactive (a highlight of path on mouseover for instance) to accentuate the dimension in focus.

Thanks Bryan, for creating these comprehensible visualizations. The biggest takeaway (for me) is that these data aren’t very interesting or compelling.

My graphic is rather small. But it looks like to LPs colored by a 1970’s hipster feeding into each other lyrics from a band named Dept. of Defense. I suspect that it is a criticism of defense department spending; but basically, I have no idea what the graphic is saying. As well, a peculiar squared area shows which is at odds with the circular flow implied by the basic idea. It appears that there are two minds working here; one has an interesting fluidity; the other this jarring block structure and dowdy font.(Me: not a designer.)