Abela’s Folly – A Thought Confuser

On the home page of my website, I quote the mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead who said, “Seek simplicity and distrust it.” This is wise advice. We want to keep things as simple as possible, but we should never oversimplify to the point of losing essential complexity. As data visualization has become increasingly popular during the last decade, efforts to explain it have often become simplistic (i.e., oversimplified) to a harmful degree. We humans long for simple answers. The world, however, is in many ways complex. Data sensemaking and presentation skills are easy to learn, and once we’ve learned them, they seem simple and even obvious, but there is no denying that the concepts, principles, and practices are complex. We should “seek simplicity and distrust it.”

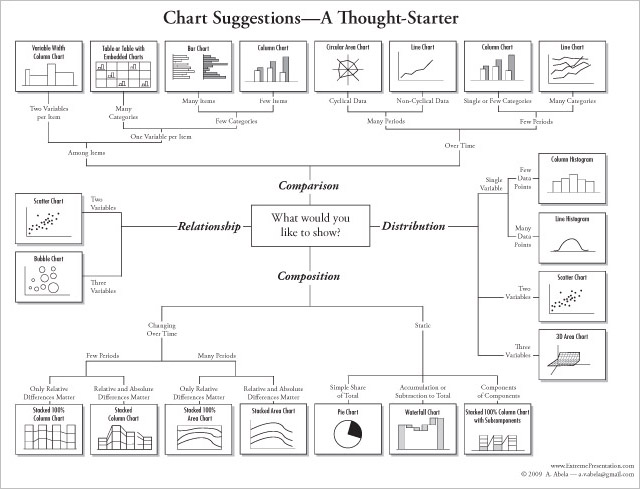

During the last year or so I’ve come across several people and organizations that were promoting the use of a chart selection diagram that was developed by Dr. Andrew Abela for his book Advanced Presentation by Design. The diagram, titled “Chart Suggestion—A Thought Starter,” serves as a guide for selecting an appropriate graph. This guide is simplistic and misleading. To be blunt, it is a confusing mess of internal contradictions and errors. While Abela might understand many aspects of effective presentation, his knowledge of data visualization is cursory at best.

Most recently, I encountered this diagram in an otherwise sane blog article by the software company iCharts. In the article, ironically titled “How to Avoid Misleading Your Audience,” they recommend the diagram as a useful guide. I responded immediately by warning them against it. Several months ago, I encountered the diagram when a fellow who was writing a book asked for my advice regarding a chapter about data visualization. He was planning to include Abela’s diagram in that chapter. Why? It conveniently fit on a page.

One-page diagrams are a tempting way to teach people new skills, but they often result in confusion. Those of you who are familiar with my work might be thinking, “But Steve, don’t you provide a one-page Graph Selection Matrix as a guide for novices?” I do provide a Graph Selection Matrix, but not as a guide for novices. I provide it as a single-page summary of the information about graph selection that’s covered in my book Show Me the Numbers. It’s only useful if you’ve already learned the concepts that it summarizes by reading the book or taking the corresponding course.

I first learned of Abela’s work several years ago when a large corporation asked me to provide ongoing data visualization training for its employees in conjunction with Abela’s presentation skills courses. Before responding to their request, I purchased and read Abela’s book. I not only found that his understanding of graphs was confused and fundamentally flawed, but also that his presentation principles were at times naïve. I told the company that I could not teach in conjunction with Abela because confusion would result.

Here’s Abela’s chart selection diagram. Take a few minutes to examine it on your own before reading my critique below. Does it make sense? Are its suggestions valid?

Where to begin? Let’s follow the sequence of choices moving outwards from the center: “What would you like to show?” We’re given four choices: 1) Comparison, 2) Distribution, 3) Composition, and 4) Relationship. This suggests that at the highest level we always want to show one of these four things in a graph. I call them “things” because I can’t think of a common term that describes these mismatched concepts. Comparison is an activity that all graphs are designed to support, Distribution is a specific feature of a set of quantitative values, Composition refers to that which something is comprised of, and Relationship is a feature that exists between values in some form or another in all data sets. These concepts don’t go together. Only one of the four—Distribution—clearly describes a specific attribute of data. Distribution refers to manner in which a set of quantitative values belonging to a single variable are distributed from lowest to highest. For example, we might want to show how employees in a company are distributed by age from youngest to oldest. Unless we need to display the distribution of a set of quantitative values (and we understand that this is what Abela means by the term distribution), the diagram leaves us hanging with no clear direction.

You might assume that Abela’s book clarifies these choices, but it doesn’t. Here’s an example of the brief explanations that his book provides: “The last option…is composition: this is when you want to highlight the components of your data.” In this context, what does “components of your data” mean? You and I might understand that he’s referring to the items that make up a categorical variable, but would someone with no training in data visualization understand this? How about the terms distribution and comparison? Abela doesn’t explain what he means by these terms at all. The closest that he comes to an adequate explanation of these high-level choices is when he provides an example of a relationship: “If you want to show that your data provides evidence of a relationship, for example, between advertising and sales revenues, then you should move to [that part of the diagram].” This reveals that by the term “relationship” he’s referring to a correlation between two or more quantitative variables, but this is certainly not the only relationship that exists in quantitative data.

If we choose Relationship, we can follow the flow diagram to the only section that provides valid graph suggestions: a Scatter Chart if we need to show a correlation between two quantitative variables and a Bubble Chart if we want to show a correlation between three variables. Other than here in this one section, Abela’s suggestions are seriously flawed.

Let’s move on to the Comparison section. Our first choice is to show comparisons Among Items or Over Time. Those of us who are experienced data analysts know that by “Items” Abela is referring to the items that make up a categorical variable, but would this be clear to a novice? “Over Time” is clear, but why do values that change over time belong to the comparison section any more than the many other comparisons that we routinely need to enable in graphs? Also, Changing Over Time, as distinct from merely Over Time, appears as a first-level choice in the Composition section, which we’ll encounter later. Suffice it to say, this is not a clear and useful taxonomy of graph types.

Let’s proceed. If we select Among Items rather than Over Time, we are then faced with the choices Two Variables per Item, which leads us to a graph that few products support and for good reason—a vertical bar graph that varies not only the heights of the bars, but also their widths to simultaneously display two quantitative variables—or One Variable per Item, which leads us to the following choice: Many Categories or Few Categories. If we select Many Categories, we are told that we should use a Table or a Table with Embedded Charts. So, according to Abela, when are tables useful? Apparently, only when we must display many categories. Oh my. What about the usefulness of tables when people need precise values? What about their usefulness when people need an easy way to look up specific values? And how do we choose between a Table and a Table of Embedded Charts? By a Table of Embedded Charts, Abela is referring to what Edward Tufte calls a small multiples display—specifically one that is arranged in both columns and rows. According to Abela, small multiples are only useful when we want to make comparisons among items, but this is hardly the case. What about a series of small multiples that are used to compare values “Over Time” rather than “Among Items,” composed of line graphs? Or what about a small multiples display of scatter plots for comparing correlations? Apparently, these aren’t appropriate options.

Onward once again. If we choose Few Categories rather than Many Categories, we must then choose between Many Items and Few Items. So, if we only need to display a few categories, what if some of them contain many items and others contain few items? What do we then? Let’s keep it simple so we can proceed. Let’s say that we need to display a single categorical variable that consists of many items, perhaps a category called product that consists of fifty individual products, rather than a category called product family that consists of only four items. In this case, according to the diagram, we should use a horizontal bar graph rather than a vertical bar graph (a.k.a., column chart). It is certainly true that it would be harder to fit fifty vertical bars side by side with their labels positioned underneath than it would to fit fifty horizontal bars one above the next with their labels positioned to the left, but is this the only circumstance that suggests an advantage of horizontal over vertical bars? How about when the labels are long and cannot be easily placed under vertical bars, but can be placed to the left of horizontal bars quite easily? If we have few items, and therefore choose vertical bars, here’s the illustration of this chart that the diagram provides:

Arranging bars to overlap is not an effective practice. Positioning them side-by-side without any overlap treats different series of bars equally and supports easy comparisons.

Let’s get through the remaining suggestions in the Comparison section and then put an end to this detailed review in favor of hitting the highlights only. If we need to show comparisons Over Time rather than Among Items, the diagram leads us to next choose between Many Periods and Few Periods, but this is a meaningless choice. Whether there are many or few periods actually has no bearing on the type of chart that we should choose in this case. For this reason, let’s skip this choice in the decision tree and go directly to the next four options: Cyclical Data, Non-Cyclical Data, Single or Few Categories, and Many Categories. Abela suggests that Cyclical Data should be displayed as a Circular Area Chart (actually illustrated by a radar chart, not an area chart), but this is rarely an effective choice. Cyclical data does not equate to a circular chart. For Non-Cyclical Data, he recommends a Line Chart, but line graphs usually work best for both cyclical and linear data. For Single or Few Categories, he recommends a Column Chart, but this is absurd. Several lines in a graph are much easier to interpret and compare than multiples sets of bars. Finally, for Many Categories, he suggests a Line Chart again, which is fine, but the number of categories does not determine the usefulness of a line graph. Line graphs excel in their ability to display patterns of change through time, which is something that bar graphs do poorly. Abela says nothing about featuring patterns of change rather than comparing values at particular points in time. The latter scenario is the only time when a bar graph should be used for a time series.

Now for the remaining highlights. In the Distribution section, a Column Histogram and a Line Histogram (i.e., a frequency polygon) are both appropriate, but the choice between them is not determined by Few Data Points vs. Many Data Points. The remaining suggestions—a Scatter Chart for Two Variables and a 3D Area Chart for Three Variables don’t belong here because they feature correlations, not distributions. In fact, a 3-D area graph is rarely useful and never for a general audience.

In the remaining Composition section, we are first asked to choose either Changing Over Time or Static. By continuing through the choices we learn that, by Composition, Abela is referring to part-to-whole displays, but none of the graphs that he goes on to suggest display parts of a whole effectively, despite the fact that people use them regularly for this purpose.

That’s it; we’re done. This diagram is not a “Thought-Starter,” as Abela suggests, but a thought confuser. This diagram was no doubt the good-intentioned attempt of Abela to help people select appropriate graphs for use in presentations. Despite his intentions, however, it fails because Abela lacks expertise in data visualization. He should have stuck to his area of expertise. He also should have never tried to squeeze chart selection guidance into a one-page diagram. Even if the diagram contained logical, well-organized, and valid suggestions, this guidance cannot be effectively conveyed in a single-page diagram without harmful reduction. Abela attributes great benefit to the single-page display as an aid to presentations. In his book, when describing the ideal length of a “conference room style presentation”—one that is designed to “engage, persuade, come to some conclusion, and drive action”—he writes:

The theoretical, ideal length of a conference room style presentation is one page—with lots of detail, well laid out. Why? Because if you can achieve the goals of your presentation in one page, why would you use two, or ten, or forty? If you are able to distill your message down to one page, your audience will get the sense that you have really captured the essence of the subject. They will also appreciate (and probably be stunned by) the brevity of your presentation.

There are, in fact, many reasons why you might choose to not squeeze everything onto a single page for your audience to view all at once. Sometimes information needs to be presented in a particular sequence, revealed one point at a time. Sometimes a single-page display “with lots of detail” will appear overwhelming, causing your audience’s attention to dissolve immediately upon showing it.

I could create a single-page diagram that provides valid graph selection guidance, but I won’t, even though I’ve been asked to do this several times. I’ve refrained because, by relying on the diagram for guidance without understanding why the recommended graph works best, novices would never learn the principles. They would forever follow a set of rules without understanding them, which isn’t enough. We don’t need an army of mindless robots. We need people who can think, who know how to apply the rules to new situations and when to break them.

My concern about Abela’s work runs deeper than his chart selection guidance. Despite much good advice, what Abela teaches in his book about presentations contains fundamental flaws. For example, the book’s first chapter instructs readers to identify the personality types of their audience, based primarily on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) assessment, so they can create a presentation that’s tailored to their audience’s preferences. (By the way, according to Myers-Briggs, I’m an INTJ, in case that matters to you.) Even if a clear set of presentation standards could be tied to each of the four Myers-Briggs personality types, which might not be possible, unless you are presenting to one person only and can get that person to take the MBTI assessment in advance, this is the most impractical suggestion I’ve ever encountered in a book about presentation skills. It’s hard to imagine that readers and students don’t raise this objection immediately upon encountering this dumbfounding advice.

People and organizations, including software vendors in the analytics space, crave shortcuts to achievement. There are efficient paths to skill development, but no shortcuts. Data sensemaking and presentation skills require learning and a great deal of practice. When we were children, our underdeveloped brains believed in magic. Just say abracadabra, rub the lamp, or wave the wand and reality will bend to your wishes. I believed that I could run faster and jump higher if my parents would only buy me a pair of tennis shoes called PF Flyers. (If you recognize the reference, you’ve been around for a while.) We who engage in data sensemaking and then work to present what we’ve found to others are no longer children. In the Bible, the following words are attributed to the Apostle Paul:

When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. (1 Corinthians 13:11; King James 2000 version)

Simplistic solutions are not the product of an adult mind. Isn’t it time to grow up?

Take care,

19 Comments on “Abela’s Folly – A Thought Confuser”

Great post, Steve. This Chart Chooser generated a v healthy, similar debate internally at Tableau a few months ago. Some people criticised it for most of the same reasons you do. Those criticisms are valid.

However, I pointed out then, and reiterate now, the impact this Chart Chooser had on me. When I was but an infant in the world of visual design, the Chart Chooser opened up a world of possibilities. I saw it and it made me realise there was method behind choosing charts. I realised there was a grammar, a hierarchy, a meaning to chart types. I printed it out and put it on my wall.

Very quickly, I realised that the branches weren’t accurate: what if I wanted to combine Relationship and Distribution? And I knew that some charts weren’t ideal: it seemed like common sense.

But the Chart Chooser was an inspiration. I didn’t take it as gospel or even as guidance for any real decisions. But it did make me think. It did make me see visualisation as a strcutured discipline. It did act as a “Thought Starter”. For that reason, I defend and promote the Chart Chooser for people starting out in this field.

Amen

(Note: To eliminate potential confusion, let me point out that Leland Wilkenson’s comment above is in response to my article, not in response to Andy’s comments, which had not yet been posted at the time.)

Andy,

I look back on my fundamentalist upbringing with great disgust and many painful memories, but I do appreciate the fact that it created the occasion for me to develop some traits and skills that have proven useful. For example, because I felt that God wanted me to become a minister, I forced myself to learn how to speak in front of groups, which was agonizing for the shy boy that I was. This ability enabled my current career, and for that I am grateful. Nevertheless, I do not praise my fundamentalist upbringing, which taught me to hate and fear people who were different from me and to shun education because it might lead me from the sacred path, nor do I recommend it to others. Praising bad advice for raising awareness that then needs to be displaced by good advice makes no sense to me. You had an epiphany when you first saw Abela’s chart chooser: “There is a logic to graph selection!” By all means, share that insight, not the bad advice. Would you praise the teacher who told your child that biological evolution is a lie of the devil merely because it provided you with an opportunity to tell her otherwise? I suspect that you would instead have a few choice words for the teacher. Hearing that you would promote Abela’s Chart Chooser for “people starting out in this field” concerns me a great deal and makes me sad. This is not the advice that Tableau Software’s data evangelist should be giving. I suspect that Leland Wilkinson, who said “Amen” above, wrote “The Grammar of Graphics,” and is your new Vice President of Statistics at Tableau, would prefer that you give impressionable novices better advice. I certainly would.

Let me clarify the last sentence in my first comment:

– “I defend it” because it reveals to people that there might be something more to data visualization than randomly choosing the prettiest chart from the Excel wizard. As a “child” in the field, this was one of several things that formed my epiphany. As I matured, I learnt to throw away my toys and move on to better models. I don’t defend the specific branches or all its specific chart types.

– “I promote it” because if it can lead others to an epiphany like mine then that is a good thing.

And then I tell them pretty much what you said. I don’t go into the depth of the reasons why it’s wrong. I tell them that as they learn and develop they will come across better guidelines and learn to think for themselves.I tell them that they too will learn to critique the Chart Chooser and create their own mental decision trees for visualising data.

Andy,

You don’t need to use something that is confusing, erroneous, and misleading — Abela’s diagram — to point out that there is a logic to chart selection. You can make this point using clear, accurate, and effective learning aids. If you learned that guns are dangerous by spending time in a war zone, would you insist that your children learn this lesson in the same way? No, you would find a way to teach this lesson that didn’t expose them to harm. You’re an evangelist. Find a better way to spread the gospel (“good news”).

Steve

I have mixed feelings about your post. On the one hand, I strongly agree with you: much of the logic behind this classification is is missing or ill-defined, comparison is used too broadly, few vs. many doesn’t make much sense and some chart types should be moved to a new high level category.

On the other hand, we should move away as soon as possible from the harmful Excel-style classification based on visual properties, towards a purpose-based classification. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe you and Andreas tried that with Chart Tamer. A purpose-based classification is much more complex, because high level categories need to be clearly defined and we must accept that most chart types can belong to more than one category.

Maybe you are right and a few well chosen learning aids are all we need, but being able to say “it’s irrelevant if you choose a bar chart or a line chart; what matters is how well your chart communicates your message” is a paradigm shift for most people new to datavis. Having a classification that uses purpose as the classifying variable can legitimate that. If Abela’s diagram is not good enough perhaps it’s time to make a better one.

@Jorge I don’t see anywhere that Steve says we shouldn’t classify chart types and their uses.

What I see is clear statement that a single page, definitive explanation of such a classification is not realistic or useful.

And that this particular classification is no good.

I think we can all agree on that much.

Jorge,

I’m not saying that we should not provide clear guidance in these matters. My career is dedicated to providing guidance of this sort. I’m arguing that we should provide guidance in a way that enables understanding. If we simply say “do this” or “don’t do that,” no conceptual learning occurs. People will follow a set of guidelines without understanding why. This isn’t the level at which people who work with data need to function. Data sensemaking and communication skills require the deeper understanding that I try to enable in my books and courses. One hundred people who rely on a diagram to select graphs cannot equal the worth of one person who understands which graphs work best for specific, sometimes nuanced situations, because he understand how and why graphs work. To promote an analytical culture, we need to approach problems as teachers, not as technicians looking for shortcuts. The reason why business intelligence technologies are still making the same unfulfilled promises to customers that they were making when the term was first coined is because they been trying to solve analytical problems as technicians with no real understanding of the problems or the people who face them.

This reminds me of your recent post regarding the marketing infographic. On one hand, we all agree that the display is poor (perhaps worse). On the other hand, some people want to defend it because it has an impact. I am firmly in the camp that this display is bad and counterproductive. I admit that a single page graphic on chart choosing may be possible, but this isn’t it.

What I find most disturbing is this trend to defend poor displays because they have led someone to an inspiration. Perhaps I am jumping (too far) to a conclusion, but it is this type of reasoning that gives us Donald Trump as a viable presidential candidate. After all, doesn’t his inflammatory comments on immigration open our eyes to important issues? Is that the standard we now apply for quality – if it causes us to think, then we applaud it?

For me, I am growing tired of justifying poor work because it makes us think. As you have said (a number of times), good work can make us think also.

I have been craving for a simple, one-page Graph Selection Matrix for years. I haven’t found one that’s useful. Now that I’ve discovered this blog, I have better insights. I saw Abela’s diagram here first, and thought, “At least it’s a starting point.”

After reading the whole blog post, I realize that there is a whole lot more to consider. I’ve ordered the Show Me the Numbers book and can’t wait for it to arrive so that I can learn the principles that Steve speaks of.

Several years ago I wrote a blog post and chart menus and chart choosers such as the one discussed here. See http://www.forbes.com/sites/naomirobbins/2011/11/29/thinking-outside-the-chart-menu/

Stumbled on this thread (a bit quiet now) in some digging around for other chart-chooser options that could be helpful job aids for people with a basic knowledge of visualization design. One that I like is Jon Schwabish & Severino Ribecca’s Graphic Continuum – less a job aid and more a visualization itself, but one of the more finessed one pagers I’ve seen of chart types. http://policyviz.com/graphic-continuum/

Amanda,

When this thread originated, one year ago, Jon Schwabish sent me an email regarding “The Graphic Continuum.” I asked him to send me an electronic copy so I could review it. He hesitated to do so, offering to mail a copy of the poster instead, because it doesn’t really qualify as a “one pager.” It requires nearly 10 times the area of a normal 8×10 inch page of paper. To save time, Jon finally sent me a link to a PDF version. Here’s what I wrote to him at the time in response:

As you probably anticipated, I can’t read the diagram. I would need to either see it printed in poster size or view it as an electronic image that could be zoomed into without losing resolution. Here are my initial thoughts, however, based on what I can see:

1. The basic taxonomy is good (i.e., distribution, time, comparing categories, geospatial, part-to-whole, and relationship), except the term “relationship” isn’t specific enough. In the relationship section you’re mixing things that don’t belong together: correlations (i.e., relationships between quantitative variables) and relationships between entities (network diagrams, etc.).

2. I can’t read the text boxes that connect various sections, but it’s hard to imagine that a flow diagram is the best way to display this information. Unlike Abela’s diagram, which he designed as a decision tree, it doesn’t look like your diagram functions as a decision tree. What I provide in “Show Me the Numbers” to serve as a chart selection guide is a matrix, which works well to show how particular chart types can be used for various purposes and under different circumstances.

As you anticipated, I don’t like the fact that you are showing a full gallery of chart types without providing any guidance regarding their effectiveness. Out of all the part-to-whole charts that you show, you’ve missed the one that’s most effective: the humble bar graph. What you’ve done creates an experience that is a lot like selecting a chart in Excel in that you are confronting the user with a host of choices without actually enabling them to choose wisely. If you are trying to help people, why are you suggesting charts that are ineffective. People don’t need a gallery of mostly bad choices. Data communication is complicated enough without over-complicating it in this way.

Loved the post and critique. I was wondering your take on this related chart: https://github.com/ft-interactive/chart-doctor/blob/master/visual-vocabulary/Visual-vocabulary.pdf that has been circulating. It seems to be a starter that requires theoretical understanding like your selection matrix. it also seems to have similar relationships to your own selection matrix. It differs in that you highlight the 4 basic geometric shapes whereas they give potential chart types.

Hi Tyler,

The Chart Doctor was clearly built on my work with acknowledging the source. It organizes graphs into the eight types that I introduced in my book Show Me the Numbers and adds one new type: flow.

The types of graphs thart are featured in their flow category don’t appear in my taxonomy of graph types because they do not feature quantitative information. Instead, these graphs — network graphs and sankey diagrmas in particular — feature connections between categorical items rather than quantitative data. Both network graphs and sankey diagrams may include quantitative information, but this is not what they feature. My taxonomy of eight types of relationships is limited to those graphs that feature quantitative relatioships, which is why it doesn’t include network graphs and sankey diagrams. The chord chart that they included as a separate graph type in the flow category is just one of many types of network graph. The waterfall chart doesn’t actually feature flow. In fact, the only graph included in the flow category that actually displays flow is the sankey diagram.

Apart from this, many of the graphs that they include are ineffective, such as donut charts, cartograms, and connected scatterplots, to name a few. Also, they placed several graphs into the wrong groups. For example, a parallel coordinates plot does not feature magnitude comparison, as they claim, but instead features a multivariate relationship.

I could go on, but suffice it to say that it would be appropriate to say to this Chart Doctor, “Physician, heal thyself.”

Hello Stephen,

I’m a avid reader of your books. I read “Show me the numbers”, “Now you see it” and both “Information Dashboard Design…” and I apply their content in my everyday work.

I’m an engineer, consulting firms in data analytics, predictive models and dashboard building.

As you, my career is built on the formality that science gave me,and the formality that scientific publications require when working on a research project. I agree with you in most of the points of your post, but I also have to admit that Abela’s book also has an impact in people not so familiarised with visualization, and helped them to start with something so simple that you don’t even question.

I came through Abela’s Chart Suggestions cheatsheet in one of my projects with a client, and of course, also read his book. In my experience, I share your thoughts and concerns about the problem of considering this as a rule of thumb for visualisation creations, but I should also state that certain audiences (business managers, corporate employees, area managers) which are not really educated under academia formality, when they first start the path of “data analysis”, find this work useful as a kickstart. Organizations are starting to embrace data at different levels, not only at IT levels which are certainly the most rigorous under data analysis, and Abela’s work has reached this audience. In this line of reasoning I came accros with a book form Scott Berinato’s called “good charts”, which mentions Abela’s work, and also (in my humble opinion) simplefies the process of visualisation selection and creation. But I think is was written with the same spirit as Abelas work, for an audience that needs to persuade people over conversations, based on insights, and not really find facts to support documented thesis.

To summarize, I see Abelas work like when they taught you Newtons fisics laws with simplified formulas (because you still do not know the mathematical tools to understand the full power of them) I think that real data analysis is not carried out by people who are looking a cheat sheet to select the chart they will use in their presentation/publication/ or dashboard. Said this, (again in my humble opinion) the audience of Abela’s work will never be in charge of creating formal dashboards or data visualisations for professional systems. We need to educate this audience in order to help their evolution.

Hello German,

You began by stating that people benefit from guidance when developing data visualization skills. This is definitely true, which is why I’ve spent the last 13 years providing this guidance. No one, however, benefits from confusing and ineffective guidance. People in need of data visualization guidance would be better off having never been exposed to Abela’s Chart Chooser because it creates confusion and it engenders ineffective practices.

People vary in the degree to which they need to develop data visualization skills. Some people require deep skills and some require only basic skills. People do not vary, however, in their need for clearly understood and effective skills. Simple, basic, understandable, and effective data visualization skills can be taught to people in effective ways. Neither Abela nor Berinato accomplish this. Instead, they create confusion, because they are confused themselves, and they promote bad practices. There is no excuse for this.

Authors, such as Abela, Berinato, and several others, along with a host of software tools that promote bad practices, have led people to believe that they are fundamentally skilled in data visualizatoin who are not. These unskilled practitioners have produced a world of “data smog.” Our world if filled with misinformation. We need clarity, truth, and understanding. Let’s not promote this further by excusing authors who claim expertise that they lack for shoddy work. People can be effectively introduced to the basic skills of data visualization in as little as two days of reading and/or training based on good resources. Given this fact, is it valid to argue for the benefits of books and courses that promote confusion and bad practices simply because they do it in less time? Something is terribly wrong if organizations are looking for ways to reduce two days of instruction to less while expecting to get good results.

Well Stephen,

Definitely I can not argue with you. You are correct in your statements.

My two cents here would be that we need to coexist with misleading content. And we need to educate users why in is wrong. I think the aim of your post is that.

Sometimes entertainment is confused with reference. As long as people understands that a cheat sheet is not knowledge, we are going to be good.

Thank you for your reply.

German,

If a cheat sheet is not knowledge, what is its purpose? Unfortunately, cheat sheets such as Abela’s Chart Chooser are promoted as knowledge, which is both deceitful and harmful. I provide a graph selection cheat sheet of sorts to students in my Show Me the Numbers course after I’ve covered the basic concepts of data visualization. It serves as a simple, abbreviated reminder of the information that they’ve learned. As such, it is useful. I don’t promote its use to people who have not taken my course or read the book “Show Me the Numbers,” because its meaning would not be clear without that context.