| |

|

|

Thanks for taking the time to read my thoughts about Visual Business

Intelligence. This blog provides me (and others on occasion) with a venue for ideas and opinions

that are either too urgent to wait for a full-blown article or too

limited in length, scope, or development to require the larger venue.

For a selection of articles, white papers, and books, please visit

my library.

|

| |

April 30th, 2013

I’ve written a great deal over the years about statistical narrative: telling stories with data. I often refer to the messages that we communicate with data as stories and talk about data analysis as the process of finding the stories that dwell in data. I describe one of the primary uses of data visualization as storytelling, but I’m a little uncomfortable when I do. Let me explain why.

A few days ago I was sent a link to an article by Saul Hymes, a medical doctor, titled “Give It Your Best Shot.” The subtitle, “A better narrative is required to counter the anti-vaccine movement’s fairy tales,” reveals the important concern that this article addresses. You’ve no doubt heard the claim that autism is caused by vaccinations. You’ve probably seen former centerfold Jenny McCarthy on TV warn against the risk of vaccinations as she tells the sad story of her autistic son, Evan. Perhaps you saw the Oprah Winfrey Show when McCarthy appeared as a guest and heard Oprah read a statement from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) that “science has shown from multiple studies that there is no evidence that vaccines cause autism.” If so, you heard McCarthy reply, “My science is Evan, and he’s at home. That’s my science,” to which the audience responded with tearful applause. McCarthy made her case with a story.

The persuasive mechanism of stories is usually emotional, not rational. Stories ordinarily move us when they tap into our feelings, not our ability to reason. Storytelling with data, when true to its purpose, however, appeals to reason, asking people to think rationally and be moved primarily by what they come to understand, not by what they feel. What Saul Hymes admits in his article, much to his discomfort as a scientist and physician, is that he sometimes gives up in his attempt to persuade patients by presenting facts and switches to stories that do an end run around reason by targeting emotions. He does it, despite his scientific perspective and reliance on evidence and reason because it gets the job done, but he does so uncomfortably.

When I tell stories with data, I often include elements that people can connect with emotionally, but I try not to rely on the power of emotion as the primary mechanism of communication and persuasion. By using emotion as the primary mechanism, I would be tapping into a lesser-evolved part of humanity, and in so doing, miss an opportunity to help people learn to make better decisions through reason. I’m not saying that emotion isn’t important and that we’d be better off without it, but instead that emotion and reason have different strengths and serve different decision-making purposes. We become our better selves when we learn to recognize this difference and put reason in the driver’s seat when it’s needed. If I appealed to emotion to win my case when reason was needed, I would achieve the desired outcome, but not in a way that would help people make better decisions on their own in the future. Fighting feeling with feeling, even when done for the greater good, would seem like a betrayal of everything that I’m striving so hard to promote in my work.

We humans have evolved in a way that enables us to think rationally, which is an amazing gift. It is because of this ability that we can develop technologies that extend our reach and we can deal with one another in ways that make the world safer and more just. When emotion ties us together in compassion and mutual respect, we benefit from our pre-human ability to feel. When emotion, however, leads us to react in hateful ways that do harm, we must learn to shift into reason and rise above our emotional instincts.

By telling stories with data that rely on evidence and reason to persuade, we can help people learn to rely on this ability more naturally and habitually. If, however, we continue to replace evidence and reason with emotion rather than using it only to complement data, we encourage humanity to remain stuck, and the world will suffer. When we visualize data using means of representation that are inaccurate and difficult to perceive in an attempt to make them eye-catching and fun, we shift the means of communication and persuasion from reason to emotion. However, when we appeal to people’s emotions strictly to help them personally connect with information and care about it, and do so in a way that draws them into reasoned consideration of the information, not just feeling, we create a path to a brighter, saner future.

Take care,

April 29th, 2013

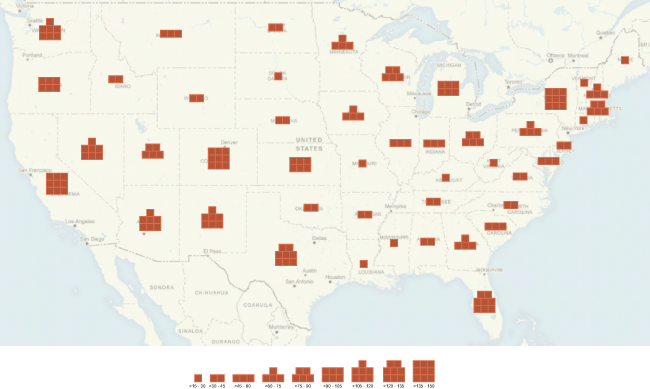

In my recent article for the Visual Business Intelligence Newsletter, titled Building Insight with Bricks, I introduced “bricks” as a new way to display quantitative values geospatially (e.g., on a map), which in theory can be read and compared more quickly and precisely than bubbles. Here’s an example:

Since the publication of the article last week, my concern for a particular limitation of this approach has grown. I mentioned in the article that bricks, unlike bubbles, do not work when they overlap. Even though I recognized this deficiency from the start, I didn’t fully appreciate at the time how much this deficiency limits the usefulness of bricks. Comments from readers, however, have raised my awareness. I especially appreciate the response from , who took the time to mock up examples of bricks vs. bubbles to illustrate the problem, and from Joe Mako, who challenged my assumption that geospatial displays don’t usually involve overlapping values.

While discussing this issue with Joe, I asserted that business uses of geospatial displays don’t typically involve overlapping values. Joe challenged my assertion, inviting me to defend it. As I began to construct my case, it gradually dawned on me that overlapping values are more prevalent than I imagined while designing bricks. This oversight occurred, not because I’m not familiar with broad and common uses of geospatial data visualization, but because I had narrowed my focus to a subset of use cases and concluded too swiftly that this subset was much larger than it actually is. I never stepped back to recognize and sufficiently test my assumption. Even an informal round of peer reviews involving some of the brightest minds in the field didn’t draw my attention to this oversight. I suffered from a blind spot while designing bricks that I never managed to correct.

Bricks are still useful; just not as broadly useful as I imagined and hoped. I failed to add as much value through the invention of bricks as I expected. I’m disappointed, but not discouraged in my effort. I was trying to solve a very real problem, and even though I’ve potentially solved it to a lesser degree than intended, I’ve succeeded more thoroughly perhaps in raising awareness about the problem. I’ll keep working on it, and I hope that you’ll join me. This is how science works. Our limited successes and even our total failures are useful and as such ought to be shared. Others can learn from our mistakes, but only if we make them known. I invite you—challenge you even—to succeed where I failed. If you do, I’ll be content that I contributed through my failure to your eventual success. After all, the benefit that our work delivers to the world is all that ultimately matters.

Take care,

April 3rd, 2013

IEEE’s VisWeek Conference, the premier international conference on visualization, includes a sub-conference on Visual Analytics Science and Technology (VAST). VAST focuses on fundamental research contributions within visual analytics as well as applications of visual analytics, including applications in science, engineering, medicine, health, media, business, social interaction, and security and investigative analysis. One of the highlights of VAST is the annual challenge that invites researchers and other experts in the field to design visualization systems to solve a particular real-world analytics problem. This year’s challenge consists of three separate mini-challenges. I think that readers of this blog might find Mini-Challenge #2 particularly interesting. Here’s how the folks who run VAST describe it:

Mini-Challenge #2 tests your skills in visual design. The fictitious Big Enterprise is searching for a design for their future situation awareness display. The company’s intrepid network operations team will use this display to understand the health, security, and performance of their entire computer network. This challenge is also very different from previous VAST Challenges, because there is no data to process and no questions to answer. Instead, the challenge is to show off your design talents by producing a creative new design for situation awareness.

Much of my work focuses on the design of situation awareness displays, called dashboards. It is particularly challenging to display a great deal of information in a way that people can use to rapidly monitor what’s going on. If you’re involved in designing displays of this type, you might want to participate in this VAST challenge. You will not only have an opportunity to get feedback from some of the world’s top experts (including myself), but could also contribute to this important field of research by demonstrating design skills that are desperately needed but seldom demonstrated.

For more information about VAST Mini-Challenge #2, visit the conference website, where you can also register if you choose to participate.

Take care,

April 1st, 2013

In response to my recent blog post about Tableau 8, largely a critique of packed bubble charts and word clouds, Chad Skelton of The Vancouver Sun wrote a rejoinder. In it he essentially endorsed my critique, but also argued that it is sometimes appropriate to use packed bubbles to present data to the general public, such as in a news publication, because “bar charts are kind of boring.”

Skelton’s assertion suggests that there is a hierarchy of interest among graphs, perhaps based on shapes and colors that are used to encode data. Can we place value-encoding objects such as rectangles (as in bars), lines, individual data points (such as dots), and circles (as in bubbles) on a continuum from boring at the low end of interest to eye-popping at the high end? Back in the 1980’s, William Cleveland and Robert McGill proposed a hierarchy of graphical methods based on empirical research, but theirs was a hierarchy of perceptibility—our ability to perceive the values represented by graphical objects easily and accurately. The utility of their hierarchy was obvious, because our ability to understand the information contained in a graph is directly tied to our ability to clearly and accurately perceive the value-encoding attributes (positions, lengths, areas, angles, slopes, color intensities, etc.). So, back to Skelton’s suggestion, is there a hierarchy of interest among graphical value-encoding methods, and, if so, does it trump perceptibility?

What is the opposite of boring that Skelton advocates? He provides a clue:

A lot of people who create data visualizations—whether reporters, non-profits or governments—are fighting tooth and nail to get people to pay attention to the data they’re presenting in an online world crowded with endless distractions. And when you’re trying to make someone take notice—especially if the subject is census data or transit figures—a little eye candy goes a long way.

Data visualizations aren’t just a way to present data. They’re often also the flashing billboard you need to get people to pay attention to the data in the first place.

Apparently, this quality of visual interest has nothing to do with the information that’s contained in a chart. Instead, in this case interest is a measure of someone’s willingness to look at a chart. The more eye-catching a chart is, the more interesting it is. It is meaningless to catch someone’s eye, however, if you fail to reveal something worth seeing. I have no problem with the fact that packed bubble charts are eye-catching; they trouble me because once they catch your eye they have little to say for themselves. A packed bubble chart is like a child that keeps screaming, “Look at me, look at me,” but just stands there with a silly grin on his face once you do. Unless you dearly love that child, the experience is just plain annoying.

The argument that a chart must exhibit eye-candy to catch the reader’s attention even when that is accomplished by displaying data in ineffective ways suffers from two fundamental problems:

- In a world of noise, screaming louder and louder is not an effective means of cutting through the noise and being heard. Screaming louder just creates more noise.

- It assumes that you cannot draw someone’s attention to a data display without using an inferior chart, one that is visually eye-catching but information-impoverished.

Regarding the first error, when people get tired of looking at lots of pretty-colored circles randomly arranged on a screen, what will we be forced to do next—make the bubbles constantly move around and spin? Regarding the second error, a graph that gets attention by displaying data in a manner that ineffectively informs is an unnecessary failure of design. Graphs can be designed to catch the eye and inform without compromise. Doing this, however, requires skill.

To make his case that packed bubble charts such as those introduced in Tableau 8 are useful to reporters such as him, Skelton shared the following example of a packed bubble chart that he published last year in The Vancouver Sun:

This chart addresses a potentially interesting topic to Vancouver’s residents, but it reveals very little. Only a few of the agency names are recognizable and only six of the bubbles include values. Had bars been used, the values wouldn’t need to be included, but there’s no way to decode values from the sizes of these bubbles. The size legend (0 through 10) on the bottom left cannot be used to interpret the values that the bubbles represent because it is one dimensional, based on length, which applies to the diameter of the bubbles, but the values are encoded by their areas, not their diameters. This chart is embarrassingly impoverished. If a reporter expressed information this miserably in words his job would be in jeopardy, but we give graphics a pass, treating them like decoration rather than content.

I wrote to Skelton and offered to demonstrate that a bar graph of this content need not be boring if he would kindly send me the information on which his packed bubbles chart was based. I requested all of the information that was available (apparently this information about public servant salaries resides in a publicly available database) about these agencies, salaries, etc., both current and past. Skelton graciously responded by sending the data, but only what he used to produce his own chart: the list of agencies and number of employees in each who earned the top 100 salaries. This information alone is of limited interest. As a Vancouver resident, I would want to know how this year was different from the past and not just the numbers of people, but also the amounts that they were paid. As Edward Tufte wrote long ago, “If the statistics are boring, then you’ve got the wrong numbers.” A chart of any type that contains this information alone will generate relatively little interest. Perhaps Skelton displayed it as packed bubbles rather than a bar graph to camouflage the fact that the information is rather limp. Dressing up a chart in glitter and spangles to generate interest that doesn’t exist in the information itself treats readers disrespectfully. In The Elements of Style, Strunk and White wrote: “No one can write decently who is distrustful of the reader’s intelligence, or whose attitude is patronizing.” I agree.

A chart that displays a rich set of interesting data will not be boring, even if it is a humble bar graph. To illustrate this fact, I began with the data that Skelton provided, and then added to it the kind of information that a journalist could include to engage the reader’s interest. (Please note that I fabricated much of the data in the display below to illustrate my point.)

This enriched set of information, displayed in a way that is easy to read, lends itself to more than a glance. It invites the reader to examine the story in depth.

Skelton is concerned with a significant challenge that journalists currently face:

For news organizations, this constant tension—between excitement and accuracy—is second nature. The most accurate way to portray a council meeting might be a photo of a bunch of bored looking seniors waiting in line to speak. But most newspapers would run the photo of the one, animated speaker waving their finger and shouting.

When did it become the job of journalism to manufacture interest and excitement that doesn’t exist and isn’t warranted? I know that news organizations are struggling to survive. I share Skelton’s concern that it is getting harder and harder to be heard in a world of increasing noise. Not every message is worth hearing, however, and when the message is worthwhile, cutting through the din in ways that rob the message of clarity and accuracy only adds to the noise.

How can reporters get people to read their stories and examine their graphs? I believe they can only do this in a lasting way by consistently providing content that is interesting, accurate, clear, and useful. If they do this often enough, they will become a trusted source. The New York Times is my primary source of news. I subscribe to this publication to show my support for expert journalism and to do what I can to keep it alive. I browse the articles on my iPad and read a few of them daily. How do I pick the articles that I read? I browse the titles, which clue me into the content. I don’t pick articles because they’re eye-catching. I pick those that are mind-catching.

Take care,

March 16th, 2013

The Big Data marketing campaign distracts us from our greatest opportunities involving data. As we chase the latest Big Data technologies to increase volume, velocity, and variety (the 3 V’s), we will never resolve the fundamental roadblocks that have been plaguing us all along. I’ve written a great deal over the last few years about the fundamental skills of data sensemaking and communication that are needed to evolve from the Data Age in which we live to the Information Age of our dreams. It is essential that we develop these basic skills, but we must face many other concerns and resolve them as well before collecting more data faster and in greater variety will matter. I recently wrote about one of those concerns in a blog post titled Big Data Disaster about the problems created by credit bureaus that shroud their scoring methodologies in mystery and have largely ignored their responsibility to base credit ratings on accurate data. We have a right to know how these bureaus determine our credit worthiness and we should never be denied opportunities due to data errors that they haven’t seriously attempted to prevent or correct. Today, I want to raise another important concern about data: the suppression of data of interest to the public. I believe in data transparency. Information that concerns us-especially that which can make the difference between health and illness, life and death-should not be held hostage and hidden. This is an ethical issue concerning our use of data. Pharmaceutical companies routinely suppress the results of unfavorable clinical trials. They even make it difficult in many cases to know that those trials were ever conducted. This results not only in a great deal of wasted research to repeatedly find what was already discovered and hidden, but also in lost lives and false hope. This suppression of data should be criminal, but it isn’t. It is, however, deeply wrong.

While teaching my workshop recently in London, one of my students recommended that I read a new book titled Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre. She did so, she said, because she saw Goldacre and me as similar in our willingness to speak out against wrong. I speak out mostly against data sensemaking technologies that fail to deliver useful functionality, but Goldacre, a medical doctor, is speaking out against a systemic problem in the pharmaceutical industry, which involves regulatory agencies, publications, and academic institutions as well. What he reveals, all based on well-documented facts, is chilling. It is an incredible example of science at its worst.

In the book’s introduction, Goldacre writes:

We like to imagine that medicine is based on evidence and the results of fair tests. In reality, those tests are often profoundly flawed. We like to imagine that doctors are familiar with the research literature, when in reality much of their education is funded by industry. We like to imagine that regulators let only effective drugs onto the market, when in reality their approve hopeless drugs, with data on side effects casually withheld from doctors and patients…

Drugs are tested by people who manufacture them, in poorly designed trials, on hopeless small numbers of weird, unrepresentative patients, and analyzed using techniques which are flawed by design, in such a way that they exaggerate the benefits of treatments. Unsurprisingly, these trials tend to produce results that favour the manufacturer. When trials throw up results that companies don’t like, they are perfectly entitled to hide them from doctors and patients, so we only ever see a distorted picture of any drug’s true effects…

Good science has been perverted on an industrial scale.

Goldacre documents the problem and its effects in great detail and goes on to describe with equal clarity what we can do to correct it.

If we wish to usher in a true information age, we must first develop an ethical approach to data, its dissemination, and use. What Goldacre reveals about the pharmaceutical industry is but one example of data being selfishly and harmfully held hostage by powerful organizations. Problems like this will go unresolved and, in fact, will never even be addressed, if we’re spending all of our time chasing Big Data. First things first; let’s learn to use data responsibly.

Take care,

|